WEEK 1

In the previous image of the page popplett.com explain in the concept map the components of the linguistics and the explication of the phonetics and phonology.

TOPIC - WEEK 2 - ARTICULATORY PHONETICS , VOCAL TRACK AND PLACE-MANNER ARTICUATION

TOPIC 1 - ARTICULATORY PHONETICS

Having preliminarily discussed vowel length and aspiration, let us now consider the sound system of English more systematically. We would like to understand what information about English pronunciation is incorporated in a speaker's knowledge of language--a central question of phonetics.

EXAMPLES:

VOCAL TRACK:

The airway used in the production of speech, especially the passage above the larynx, including the pharynx, mouth,and nasal cavities.:

EXAMPLE:

ENGLISH VOWELS:

English Vowel Sounds:

A vowel letter can represent different vowel sounds: hat [hæt], hate [heit], all [o:l], art [a:rt], any ['eni].

The same vowel sound is often represented by different vowel letters in writing: [ei] they, weigh, may, cake, steak, rain.

Open and closed syllables:

Open syllable: Kate [keit], Pete [pi:t], note [nout], site [sait], cute [kyu:t].

Closed syllable: cat [kæt], pet [pet], not [not], sit [sit], cut (the neutral sound [ə]).

Vowels and vowel combinations:

The vowels A, E, I, O, U, Y alone, in combination with one another or with R, W represent different vowel sounds. The chart below lists the vowel sounds according to the American variant of pronunciation.

| Sounds | Letters | Examples | Notes |

| [i:] | e, ee ea ie, ei | be, eve, see, meet, sleep, meal, read, leave, sea, team, field, believe, receive | been [i]; bread, deaf [e]; great, break [ei]; friend [e] |

| [i] | i y | it, kiss, tip, pick, dinner, system, busy, pity, sunny | machine, ski, liter, pizza [i:] |

| [e] | e ea | let, tell, press, send, end, bread, dead, weather, leather | meter [i:] sea, mean [i:] |

| [ei] | a ai, ay ei, ey ea | late, make, race, able, stable, aim, wait, play, say, day, eight, weight, they, hey, break, great, steak | said, says [e]; height, eye [ai] |

| [æ] | a | cat, apple, land, travel, mad; AmE: last, class, dance, castle, half | |

| [a:] | ar a | army, car, party, garden, park, father, calm, palm, drama; BrE: last, class, dance, castle, half | war, warm [o:] |

| [ai] | i, ie y, uy | ice, find, smile, tie, lie, die, my, style, apply, buy, guy | |

| [au] | ou ow | out, about, house, mouse, now, brown, cow, owl, powder | group, soup [u:] know, own [ou] |

| [o] | o | not, rock, model, bottle, copy | |

| [o:] | or o aw, au ought al, wa- | more, order, cord, port, long, gone, cost, coffee, law, saw, pause, because, bought, thought, caught, hall, always, water, war, want | work, word [ər] |

| [oi] | oi, oy | oil, voice, noise, boy, toy | |

| [ou] | o oa, ow | go, note, open, old, most, road, boat, low, own, bowl | do, move [u:] how, owl [au] |

| [yu:] | u ew eu ue, ui | use, duty, music, cute, huge, tune, few, dew, mew, new, euphemism, feud, neutral, hue, cue, due, sue, suit | |

| [u:] | u o, oo ew ue, ui ou | rude, Lucy, June, do, move, room, tool, crew, chew, flew, jewel, blue, true, fruit, juice, group, through, route; AmE: duty, new, sue, student | guide, quite [ai]; build [i] |

| [u] | oo u ou | look, book, foot, good, put, push, pull, full, sugar, would, could, should | |

| neutral sound [ə] | u, o ou a, e o, i | gun, cut, son, money, love, tough, enough, rough, about, brutal, taken, violent, memory, reason, family | Also: stressed, [ʌ]; unstressed, [ə]. |

| [ər] | er, ur, ir or, ar ear | serve, herb, burn, hurt, girl, sir, work, word, doctor, dollar, heard, earn, earnest, earth | heart, hearth [a:] |

A speech sound that's not a vowel.

A consonant is a letter of the alphabet that represents a speech sound produced by a partial or complete obstruction of the air stream by a constriction of the speech organs.

EXAMPLE:

MINIMAL PAIRS:

A minimal pair is a pair of words that vary by only a single sound, usually meaning sounds that may confuse English learners, like the /f/ and /v/ infan and van, or the /e/ and /ɪ/ in desk and disk

EXAMPLE:

DIPTHONGS:

A gliding monosyllabic speech sound (as the vowel combination at the end of toy) that starts at or near the articulatory position for one vowel and moves to or toward the position of another

EXAMPLE:

TRIPHTHONGS:

A compound vowel sound resulting from the succession of three simple ones and functionig as a unit.

EXAMPLE:

SYLLABES:

an uninterrupted segment of speech consisting of a vowel sound, adiphthong, or a syllabic consonant, with or without preceding orfollowing consonant sounds:

EXAMPLES:

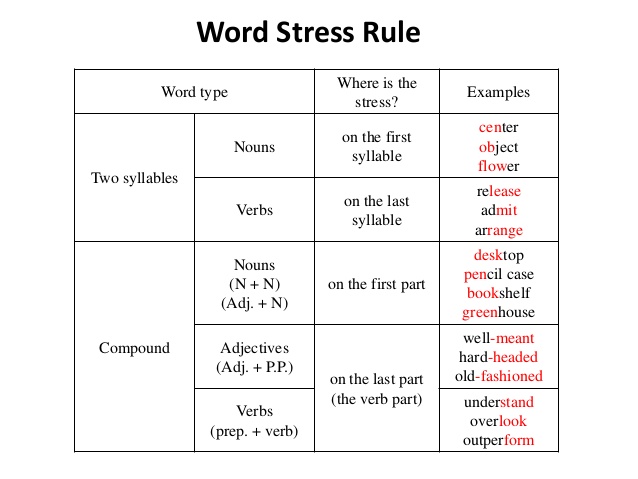

WORD STRESS:

the stress accent on the syllables of individual words either in a sentence or in isolation

EXAMPLE:

ASSIMILATION:

the act or process by which a sound becomes identical withor similar to a neighboring sound in one or more defining characteristics, as place of articulation, voice or voicelessness, or manner of articulation.

EXAMPLE:

PROSODY:

the stress and intonation patterns of an utterance.

EXAMPLE:

INTONATION:

the sound changes produced by the rise and fall othe voice when speaking, especially when this has an effect on the meaning of what is said:

CONNECTED SPEECH:

When we speak naturally we do not pronounce a word, stop, then say the next word in the sentence. Fluent speech flows with a rhythm and the words bump into each other. To make speech flow smoothly the way we pronounce the end and beginning of some words can change depending on the sounds at the beginning and end of those words.

EXAMPLE:

ENGLISH VOWEL SYSTEM: - WEEK 2

LONG AND SHORT VOWELS:

When a vowel sounds like its name, this is called a long sound. A vowel letter can also have short sounds. Whether a vowel has a long sound, a short sound, or remains silent, depends on its position in a word and the letters around it. Click on the following vowel letters to hear their long and short sounds.

EXAMPLES:

Now this is my video explication in and summary about in the topic:

CONSONANTS CLUSTERS - WEEK 3 AND 5

A group of two or more consonant sounds that come before (onset), after (coda), or between (medial) vowels. Also known as cluster.

EXAMPLES:

Observations:

- "The combination /st/ is a consonant cluster (CC) used as onset in the word stop, and as coda in the word post. There are many CC onset combinations permitted in English phonotactics, as in black,bread, trick, twin, flat and throw. . . .

"English can actually have larger onset clusters, as in the words stress and splat, consisting of three initial consonants (CCC). The phonotactics of thee larger onset clusters is not too difficult to describe. The first consonant must always be /s/, followed by one of the voiceless stops (/p/, /t/, /k/) and a liquid or glide (/l/, /r/, /w/). You can check if this description is adequate for the combinations in splash,spring, strong, scream and square."

(George Yule, The Study of Language, 4th ed. Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010)

"In some instances the consonant cluster may coincide with a cluster which can occur at the end of a word without a suffix; for example the words lapseand laps end with the same consonant cluster and in fact are homophonous, and the same is true ofchaste and chased." (Charles W. Kreidler, The Pronunciation of English: A Course Book. Blackwell, 2004)

- Consonant Cluster Reduction:

- "Consider the example of word-final consonant cluster reduction as it affects sound sequences such as st, nd, ld, kt, and so forth in various English dialects. The rule of word-final consonant cluster reduction may reduce items such as west, wind, cold, and act to wes', win', col', and ac' respectively. The incidence of reduction is quite variable, but certain linguistic factors systematically favor or inhibit the operation of the reduction process. . . . With respect to the phonological environment that follows the cluster, the likelihood of reduction is increased when the cluster is followed by a word beginning with a consonant. This means that cluster reduction is more frequent in contexts such aswest coast or cold cuts than in contexts like west end or cold apple."

(Walt Wolfram, "Dialect in Society." The Handbook of Sociolinguistics, ed. by Florian Coulmas. Blackwell, 1997)

- "Consonant cluster reduction is a process in which the final consonant group or cluster, composed of two consonant sounds, is reduced to a single consonant sound. . . . As a result of the consonant cluster process, the words tes ('test') and des ('desk') rhyme, and are minimally different in that they contrast only in the initial t and d sounds."

(Lisa J. Green, African American English: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge University Press, 2002)

EXAMPLES:

CONSONANT SOUNDS PRODUCE AND CLASSIFICATED - WEEK 4

A consonant is a letter of the alphabet that represents a speech sound produced by a partial or complete obstruction of the air stream by a constriction of the speech organs.

CLASSIFICATION:

- "The 24 usual consonants occur in the following words, at the beginning unless otherwise specified: pale, tale, kale, bale, dale, gale, chain, Jane, fail, thin, sale, shale, hale, vale, this, zoo; (in the middle of) measure, mail, nail; (at the end of) sing, lay, rail, wail, Yale. Not one of these consonants is spelled in a completely consistent way in English, and some of them are spelled very oddly and inconsistently indeed. Note that our alphabet has no single letters for spelling the consonants in chain, thin, shale, this, measure, and sing. Those letters that are commonly used for spelling consonants may be called consonant letters, but calling them consonants is loose and misleading."

- (12 , Harper, 2006)

In the following video I explain some examples about the previous topic keep in mind the chart 13 that is into of webgraphy information:

MINIMAL PAIRS VS DIPHTONGS AND TRIPHTONGS - WEEK 6

This is my map about the topic realized by picktochart:

MINIMAL PAIRS VS DIPHTONGS AND TRIPHTONGS - WEEK 6

This is my map about the topic realized by picktochart:

SYLLABLES AND WORD STREESS - WEEK 8:

1 WHAT IS THE SYLLABLES?

One or more letters representing a unit of spoken language consisting of a single uninterrupted sound. Adjective: syllabic.

A syllable is made up of either a single vowel sound (as in the pronunciation of oh) or a combination of vowel and consonant(s) (as in no and not).

A syllable that stands alone is called a monosyllable. A word containing two or more syllables is called a polysyllable.

- The Parts of a Syllable

- "Syllable isn't a tough notion to grasp intuitively, and there is considerable agreement in counting syllables within words. Probably most readers would agree that cod has one syllable, ahi two, and halibut three. But technical definitions are challenging. Still, there is agreement that a syllable is a phonological unit consisting of one or more sounds and that syllables are divided into two parts--an onset and a rhyme. The rhyme consists of a peak, or nucleus, and any consonants following it. The nucleusis typically a vowel . . .. Consonants that precede the rhyme in a syllable constitute the onset . . .

"The only essential element of a syllable is a nucleus. Because a single sound can constitute a syllable and a single syllable can constitute a word, a word can consist of a single vowel--but you already knew that from knowing the words a and I."27

- "The word strengths may have the most complex syllable structure of any English word: . . . with three consonants in the onset and four in the coda [the consonants at the end of the rhyme]!"28 - Vowels and Consonants

"Some consonants can be pronounced alone (mmm, zzz), and may or may not be regarded assyllables, but they normally accompany vowels, which tend to occupy the central position in a syllable (the syllabic position), as in pap, pep, pip, pop, pup. Consonants occupy the margins of the syllable, as with p in the examples just given. A vowel in the syllable margin is often referred to as aglide, as in ebb and bay. Syllabic consonants occur in the second syllables of words like middle ormidden, replacing a sequence of schwa plus consonant . . .."29 - Reduplication

"[A] common syllable process, especially among the child's first 50 words, is reduplication (syllable repetition). This process can be seen in forms like mama, papa, peepee, and so on. Partial reduplication (the repetition of part of a syllable) may also occur; very often an /i/ is substituted for the final vowel segment, as in mommy and daddy." 30

For example:

- 2 WHAT IS THE WORD STRESS?

- In English, we do not say each syllable with the same force or strength. In one word, we accentuate ONE syllable. We say onesyllable very loudly (big, strong, important) and all the other syllables very quietly.Let's take 3 words: photograph, photographer andphotographic. Do they sound the same when spoken? No. Because we accentuate (stress) ONE syllable in each word. And it is not always the same syllable. So the "shape" of each word is different.

- This happens in ALL words with 2 or more syllables: TEACHer, JaPAN, CHINa, aBOVE, converSAtion, INteresting, imPORtant, deMAND, etCETera, etCETera, etCETeraThe syllables that are not stressed are weak or small or quiet. Fluent speakers of English listen for the STRESSED syllables, not the weak syllables. If you use word stress in your speech, you will instantly and automatically improve your pronunciation and your comprehension.Try to hear the stress in individual words each time you listen to English - on the radio, or in films for example. Your first step is to HEAR and recognise it. After that, you can USE it!There are two very important rules about word stress:

- One word, one stress. (One word cannot have two stresses. So if you hear two stresses, you have heard two words, not one word.) 31

- The stress is always on a vowel. For examples:

The following spider map explain the topic:

WEAK FORMS, ELISION AND ASSIMILATION- WEEK 8:

ASSIMILATION:

A general term in phonetics for the process by which a speech sound becomes similar or identical to a neighboring sound. In the opposite process, dissimilation, sounds become less similar to one another.

"Assimilation is the influence of a sound on a neighboring sound so that the two become similar or the same. For example, the Latin prefix in- 'not, non-, un-' appears in English as il-, im-. and ir- in the wordsillegal, immoral, impossible (both m and p are bilabial consonants), and irresponsible as well as the unassimilated original form in- in indecent and incompetent. Although the assimilation of the n of in- to the following consonant in the preceding examples was inherited from Latin, English examples that would be considered native are also plentiful. In rapid speech native speakers of English tend to pronounce ten bucks as though it were written tembucks, and in anticipation of the voiceless s in son the final consonant of his in his son is not as fully voiced as the s in his daughter, where it clearly is [z]." 33

Direction of Influence

"Features of an articulation may lead into (i.e. anticipate) those of a following segment, e.g. English white pepper /waɪt 'pepə/ → /waɪp 'pepə/. We term this leading assimilation.

"Articulation features may be held over from a preceding segment, so that the articulators lag in their movements, e.g. English on the house /ɑn ðə 'haʊs/ → /ɑn nə 'haʊs/. This we term lagging assimilation.

"In many cases there is a two-way exchange of articulation features, e.g. English raise your glass /'reɪz jɔ: 'glɑ:s/ → /'reɪʒ ʒɔ: 'glɑ:s/. This is termed reciprocal assimilation."34

Alveolar Nasal Assimilation: "I ain't no ham samwich"

"Many adults, especially in casual speech, and most children assimilate the place of articulation of the nasal to the following labial consonant in the word sandwich:

sandwich /sænwɪč/ → /sæmwɪč/The alveolar nasal /n/ assimilates to the bilabial /w/ by changing the alveolar to a bilabial /m/. (The /d/ of the spelling is not present for most speakers, though it can occur in careful pronunciation.)"35

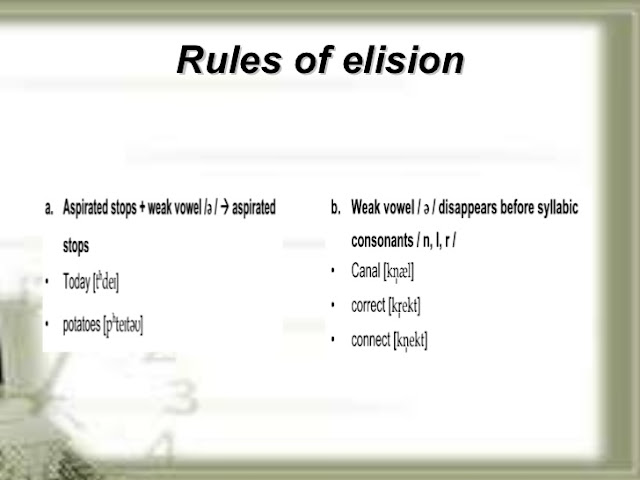

ELISION:

In phonetics and phonology, the omission of a sound (a phoneme) in speech. Elision is common in casual conversation.

More specifically, elision may refer to the omission of an unstressed vowel, consonant, or syllable. This omission is often indicated in print by an apostrophe.

"Elision of sounds can . . . be seen clearly in contracted forms like isn't (is not), I'll (I shall/will), who's (who is/has), they'd (they had, they should, or they would), haven't (have not) and so on. We see from these examples that vowels or/and consonants can be elided. In the case of contractions or words like library(pronounced in rapid speech as /laibri/), the whole syllable is elided." 37

The Nature of Reduced Articulation

"It is easy to find examples of elision, but very difficult to state rules that govern which sounds may be elided and which may not. Elision of vowels in English usually happens when a short, unstressed vowel occurs between voiceless consonants, e.g. in the first syllable of perhaps, potato, the second syllable ofbicycle, or the third syllable of philosophy.38

"It is easy to find examples of elision, but very difficult to state rules that govern which sounds may be elided and which may not. Elision of vowels in English usually happens when a short, unstressed vowel occurs between voiceless consonants, e.g. in the first syllable of perhaps, potato, the second syllable ofbicycle, or the third syllable of philosophy.38

WEAK FORMS:

Weak forms are syllable sounds that become unstressed in connected speech and are often then pronounced as a schwa.

Example

In the sentence below the first 'do' is a weak form and the second is stressed.

In the sentence below the first 'do' is a weak form and the second is stressed.

What do you want to do this evening?

In the classroom

Structural words, such as prepositions, conjunctions, auxiliaries and articles are often pronounced in their weak form, since they do not carry the main content, and are therefore not normally stressed. Learners can find them difficult to hear and this interferes with understanding. Counting the number of words in a sentence, or sentence dictations can help raise awareness of weak forms. 41

EXAMPLES:Structural words, such as prepositions, conjunctions, auxiliaries and articles are often pronounced in their weak form, since they do not carry the main content, and are therefore not normally stressed. Learners can find them difficult to hear and this interferes with understanding. Counting the number of words in a sentence, or sentence dictations can help raise awareness of weak forms. 41

In the following spidermap explain the topic corresponding of the WEEK 8:

for view better the spider map this is the website:

https://bubbl.us/?h=2d1b9d/5a9cb1/29GWVDx8QaK0I&r=460553451

PROSODY - WEEK 9

What is Prosody?

One way to appreciate prosody is

to listen to sentences where the prosody is not quite right. For this, we'd

like you to meet two robots, each with differently deficient prosody: R1D1 has

defective speech rhythm. R1P1 has defective pitch control.

Duration

|

R1D1 is playful

|

R1D1 has two moods: when he is playful, he picks a random

number between 10 and 400 milliseconds and use that for the phone duration.

|

|

R1D1 is serious

|

When he is serious, he assigns the same duration value to

each phone.

|

||

Pitch

|

R1P1 is playful

|

R1P1 doesn't know how to control pitch: when he is

playful, he creates random melody for his sentence.

|

|

R1P1 is serious

|

When he is serious, he uses the same pitch values, or

monotone.

|

Viewed in the large, prosody is a parallel channel for communication, carrying some information that cannot be simply deduced from the lexical channel. All aspects of prosody are transmitted by muscle motions, and in most of them, the recipient can perceive, fairly directly, the motions of the speaker. Even in intonation, pitch has a fairly smooth relationship to the underlying muscle tensions.

While pitch is an important component of prosody, it has been known since the 1950s (Fry, 1955; Fry, 1958; Bolinger, 1958; Lieberman, 1960; Hadding-Koch, 1961) that duration and amplitude are also important components. Recent literature (Maekawa, 1998; Kehoe et al., 1995; Sluijter and van Heuven, 1996; Pollock et al., 1990; Sluijter et al., 1997; Turk and Sawusch, 1996, Erickson, 1998 and references therein) also provides support for amplitude, spectral tilt and jaw movement as important components of prosody.

Clearly, with our broad definition of prosody, hand gestures, eyebrow and face motions, can be considered prosody, because they carry information that modifies and can even reverse the meaning of the lexical channel. In this tutorial, however, we concentrate on pitch (f0) modeling.

Prosody, as expressed in pitch, gives clues to many channels of linguistic and para-linguistic information. Linguistic functions such as stress and tone tend to be expressed as local excursions of pitch movement. Intonation types and para-linguistic functions may affect the global pitch setting, in addition to characteristic local pitch excursion near the edge of the sentence (i.e. boundary tones).

- Prosody used to convey lexical meaning: Stress,

accentual and tone languages.

- Stress: English is an example of a stress

language. Stress location is part of the lexical entry of each English

word. For example, "apple" and "orange" both have

stress on the first syllable, while "banana" has stress on the

second syllable. When an English word is spoken in isolation in

declarative intonation, f0 typically peaks on the stressed syllable.

- Accentual language: Japanese is an example of an

accentual language. A word

is lexically marked as accented (on a particular syllable) or un-accented. A simplified description is that

pitch rises near the beginning of

an accentual phrase and falls on the accented syllable. For detailed

analysis, see Beckman and Pierrehumbert (1988).

- Tone language: Mandarin Chinese is an example of

a lexical tone language. Each syllable is lexically marked with one of

the four lexical tones (and occasionally, with a fifth, neutral tone).

Tones have distinctive pitch contours. Altering the pitch contour may

have the consequence of changing the lexical meaning of a word, and

perhaps the meaning of a sentence.

- Prosody used to convey non-lexical information:

Intonation type (Question vs. declarative sentences).

Languages

may employ prosody in different ways to differentiate declarative sentences

from questions. A general trend is that questions are associated with higher

pitch somewhere in the sentence, most commonly near the end. This may be

manifested as a final rising contour, or higher/expanded pitch range near the

end of the sentence. In English, declarative intonation is marked by a falling

ending while yes-no question intonation is marked by a rising one, as shown on

the last digit "one" in the English examples. Russian question, on

the other hand, uses strong emphasis on a key word instead of a rising tail.

Chinese questions are manifested by an expanded pitch range near the end of the

sentences, however, the speaker preserves the lexical tone shapes (Yuan, Shih,

Kochanski 2002).

Examples of

declarative and question intonation in

English, Russian, and Chinese.

- Prosody used to convey discourse functions:

Focus, prominence, discourse segments, etc.

Topic

initialization is typically associated with high pitch (Hirschberg and

Pierrehumbert, 1986; Sluijter and Terken, 1993). Pitch is typically raised in

the discourse initial section and lowered in the discourse final section.

Also,

new information in the discourse structure is typically accented while old

information de-accented.

- Prosody used to convey emotion.

Most

experiments studying emotional speech study stylized emotion, as delivered by

actors and actresses. In these acted-out emotions, a few categories of emotions

can be reliably identified by listeners, and one can find consistent acoustic

correlates of these categories. For example, excitement is expressed by high

pitch and fast speed, while sadness is expressed by low pitch and slow speed.

Hot anger is characterized by over-articulation, fast, downward pitch movement,

and overall elevated pitch. Cold anger shares many attributes with hot anger,

but the pitch range is set lower.

The

study of emotion in natural speech is a lot more complicated. It is generally

recognized that speakers show mixed feelings and ambiguous states of mind, and

the emotions do not fall into clear cut categories.

Emotion

experiment stimuli

- Couldn't

you walk home alone, Uncle Oliver?

- Shall I

take my gun, or fishing rod?

- Marilyn

won nine million dollars

- Dirty

rats are the best, aren 't they?

- Prosody tied to the physical system: declination.

There

is a tendency for pitch to decline during the course of an utterance ('t Hart

and Cohen, 1973; Maeda, 1976). This effect is at least partially caused by the

drop of sub-glottal pressure (Lieberman, 1967; Fujisaki, 1983; Strik and Boves,

1995). Listeners compensate for this effect: When presented with two accented

words of equal pitch height, listeners judge the second one to be more

prominent (Pierrehumbert 1979).

Below

is an example of Mandarin Chinese (Shih, 2000) showing the pitch declination

profile in a sequence of high level tones, which are marked as "H" in

the figure. The pitch drops about 50 Hz from the highest "H" to the

final "H".

INTONATION - WEEK 10

Intonation

Intonation describes how the voice rises and falls in

speech. The three main patterns of intonation in English are: falling intonation, rising intonation and

fall-rise intonation.

Falling intonation

Falling intonation describes how the voice falls on the

final stressed syllable of a phrase or a group of words. A falling intonation

is very common in wh-questions.

EXAMPLES:

Where’s the nearest p↘ost-office?

What time does the

film f↘inish?

We also use falling intonation when we say something

definite, or when we want to be very clear about something:

EXAMPLE:

I think we are

completely l↘ost.

OK, here’s the magaz↘ine you wanted.

Rising intonation:

Rising intonation describes how the voice rises at the end

of a sentence. Rising intonation is common in yes-no questions:

EXAMPLES:

I hear the Health

Centre is expanding. So, is that the new d↗octor?

Are you th↗irsty?

Fall-rise intonation describes how the voice falls and then

rises. We use fall-rise intonation at the end of statements when we want to say

that we are not sure, or when we may have more to add:

EXAMPLE:

I do↘n’t support any football team at the

m↘om↗ent.

(but I may change my mind in future).

It rained every day

in the firs↘t w↗eek. (but things improved after

that).

We use fall-rise intonation with questions, especially when

we request information or invite somebody to do or to have something. The

intonation pattern makes the questions sound more polite:

EXAMPLE:

Is this your cam↘er↗a?

Would you like

another co↘ff↗ee?

TONE AND TONE

LANGUAGE

Tone, in linguistics,

a variation in the pitch of the voice while speaking. The word tone is usually

applied to those languages (called tone languages) in which pitch serves to

help distinguish words and grammatical categories—i.e., in which pitch

characteristics are used to differentiate one word from another word that is

otherwise identical in its sequence of consonants and vowels.

For example:

PRINCIPLES OF THE CONNECTED SPEECH AND SONG THE HALLOWEEN - WEEK 14:

Week 4 – Connected speech processes and the principles of English spelling

1

Connected Speech Processes

What are

connected speech processes?

Connected speech

processes are changes in the pronunciation of words when they are in a

sentence. So far, we have only really

considered the sounds of words in isolation but today we will consider what

happens when words are joined together to make sentences. Each type of change has a different

name. We will consider assimilation,

elision and r-sandhi.

1.1 Assimilation

Sounds that belong to one word can cause

changes in sounds belonging to other words.

When a word’s pronunciation is affected by sounds in a neighbouring

word, we call this process assimilation.

We find that sounds in the affected word become more like sounds in the

neighbouring word. The two sounds can

become more alike in terms of voice, place or manner. Assimilation occurs when speech is rapid and

casual. Changes in sound that occur in

rapid speech are said to be due to gradation.

Direction of

change

If a phoneme is affected by one than comes

later in the sentence, the assimilation is termed regressive. If a phoneme is affected by one that came

earlier in the utterance, the assimilation is termed progressive.

If a phoneme is affected by one than comes

later in the sentence, the assimilation is termed regressive. If a phoneme is affected by one that came

earlier in the utterance, the assimilation is termed progressive.

1.1.1 Assimilation of voice

Across word

boundaries

In English, only regressive assimilation is

found across word boundaries and then only when a voiced word final consonant

is followed by a voiceless word initial consonant.

Example:

Ø

big cat bIg kQt > bIk kQt

It is never the case that a word final

voiceless consonant becomes voiced because of a word initial voiced consonant

(although this does happen in many languages).

Across

morpheme boundaries

When a noun is pluralised by adding a

n<s> suffix the pronunciation of the <s> depends on the voicing of

the final consonant of that noun. If the

final consonant is voiced, the suffix will be pronounced as [z], if the final

consonant is voiceless, the suffix will be pronounced as [s]. As an earlier consonant affects a later one,

this is an example of progressive assimilation.

This process in fixed in English as there are hardly any exceptions.

Examples:

Ø

Cats kQts voiceless

final consonant and suffix

Ø

Dogs dgz voiced

final consonant and suffix

The same is true when an <s> is added

to a noun to make a possessive suffix or to a verb to make the third person

singular suffix.

Examples:

Possessive

Ø

Jack’s dZQks voiceless

final consonant and suffix

Ø

John’s dZnz voiced

final consonant and suffix

Third person singular

Ø

She jumps dZÃmps voiceless

final consonant and suffix

Ø

She runs rÃnz voiced

final consonant and suffix

1.1.2

Assimilation of Place

Across word

boundaries

In English, assimilation of place only

occurs regressively across word boundaries and only with the alveolar

consonants (including clusters of alveloars).

Examples:

Ø

That person DQt pÎ:sn DQp pÎ:s«n final

alveolar changes to bilabial

Ø

That thing DQt TIN DQt 9TIN final

alveolar changes to dental

Ø

Good night gUd gÎl gUg gÎ:l final

alveolar changes to velar

The alveolar fricatives s and z change to S and Z respectively when followed by j or S

Examples:

Ø

This shoe DIs Su > DIS Su (regressive)

Ø

Those years D«Uz jI«z > D«UZ jI«z (regressive)

Within words

Within codas, if

a nasal comes before a plosive or a fricative, its place of articulation is

determined by that of the other consonant.

This process is fixed in English as there are very few exceptions.

Examples:

Bump bÃmp bilabial nasal

and plosive

Bank bQNk velar nasal and

plosive

Hunt hÃnt alveolar nasal

and plosive

1.1.3

Assimilation of manner

Assimilation of manner is only found in

very fast casual speech. In general

speakers change sounds to sounds that are ‘easier’, those that obstruct the

airflow less and therefore require less energy.

Examples:

Ø

Good night gUd naIt > gUn naIt a

final plosive becomes a nasal (regressive)

Ø

That side DQt saId > DQs saId a

final plosive becomes a fricative (regressive)

Ø

Read these ri:d

Di:z

> ri:d9 d9i:z an initial fricative becomes a plosive

(progressive), this only happens when a word final nasal or plosive is followed

by a word initial D

1.1.4 Coalescence

Coalescence is a special type of

assimilation process. In coalescence,

the process of assimilation is bi-directional and two segments combine to

produce one. In English this often

happens when an alveolar plosive is followed by a palatal approximant (j) and

they combine to form a palato-alveolar affricate.

Example:

Ø

Did you dId ju: > dIdZu:

1.2 Elision

Elision is the loss of a phoneme. In technical language we say that the phoneme

is deleted or is realised as zero.

Elision occurs more in fast casual speech, thus elision is a process of

gradation. There are many examples of

elision in English, a few are given below.

Example:

Loss of a weak vowel after voiceless

plosives (p, t, k)

Ø

Potato p«teIt«U > pHteIt«U (schwa is lost, p is aspirated)

Avoidance of complex clusters

Ø

George the sixths throne sIksTs Tr«Un > sIksTr«Un

Loss of final v in ‘of’ before consonants

Ø

Lots of them lts «v D«m > lts «

D«m

1.3

r sandhi

Sandhi is a process where a sound is

modified when words are joined together

Some linguists distinguish two types of r sandhi,, linking and intrusive

r.

1.3.1 Linking r

You will remember that for speakers of

non-rhotic accents r is not pronounced after vowels. So the pronunciations of ‘car’ is kA: and of ‘more’ is m:

However, in these accents, when words that are spelled ending with an

<r> or an <re> come before a word beginning with a vowel, the r is

usually pronounced. This is linking

r. In rhotic accents the r is also

pronounced when the words are in isolation so cannot be termed linking.

Examples:

Ø

Far away fA: «wQy > fAr «wQy

Ø

More ice m: aIs > m:r aIs

1.3.2

Intrusive r

Intrusive r also involves the pronunciation

of an r sound, but this time there is no justification from the spelling as the

word’s spelling does not end in <r> or <re>. Again this relates to non-rhotic accents;

rhotic accents do not have intrusive r.

Ø

The idea of it aIdI« «v It > aIdI«r «v It

2

The Principles of English Spelling

Differences of

accent can complicated the process of learning to spell (particularly use of

rhoticity and vowels). What is clear is

that English is not entirely regular.

Although there are lots of rules, there are many words which do not

follow them. The following sections

discuss some of the sources of irregularity.

2.1 Old English

The problems

began when Christian missionaries began to use their 23 letter alphabet to

represent the 35 phonemes of Old English.

This meant that some letters had to be used for more than one sound, for

example <c> represented /k/ and /s/ introducing complications and

irregularities.

2.2 Middle English

After the Norman

Conquest French scribes brought many French spelling conventions to written

English

<qu>

replaced Old English <cw> e.g.‘quick’

<gh>

replaced <h> e.g. ‘night’

<u> looked

similar to written <v>, <m> and <n> so they replaced it with

<o> in cases where it followed these letters ‘love’, ‘come’, ‘son’

When Caxton

brought his printing press to London , spelling

gradually became stabilised and the London

2.3 Early Modern English

Although

printing had stabilised spelling, pronunciation was still changing. During the Great Vowel Shift the English long

vowels underwent huge changes. However,

because printing had already established spelling conventions, the spelling of

many words now reflects a much older pronunciation. For example, in Chaucer’s day, the vowel in

‘name’ was /A:/ but

this changed to /eI/ during the shift. The

spelling still reflects the older pronunciation. The shift affected all the English long

vowels.

Silent letters

are a similar case. Letters such as

<k> in ‘knee’ and <e> in ‘time’ were pronounced at the time

spelling was standardised but were lost from pronunciation later on.

2.3.1 Etymology

In the 16th

century many scholars decided that spelling should be altered to reflect the

roots of words. So, for example, a

<b> was added to ‘debt’ to reflect its origins in the Latin word

‘debitum’.

2.3.2 Borrowings

In the 16th

and 17th centuries, many non-English words were introduced into the

language from French, Latin, Greek, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese. Often the spelling was left unchanged from

the foreign spelling. The problem

continues today as we still borrow extensively (think about ‘quesadillas’).

2.4 Rules and regularity

Despite all this

irregularity, there are many regular aspects to English spelling. To give one example, consider the English

vowel sounds and spellings. In English

the letters <a> <e> <i> and <u> all have to represent

two vowels, one short and one long (or diphthongal).

<a> eI as in ‘cape’ Q as in ‘mat’

<e> i: as in ‘meter’ e as in ‘met’

<i> aI as in ‘line’ I as in ‘bit’

<o> «U as in ‘go’ as in ‘pot’

<u> u: as in ‘lucid’ Ã as in ‘cut’

There is,

however, regularity to some extent as the length of the vowel is usually

indicated by either:

Ø Consonant doubling indicates a short preceding vowel cp. ‘coma’ and

‘comma’

or

Ø A final <e> after a consonant marks the previous vowel as long

cp. ‘win’ and ‘wine’(49)(50)

SONG: THE HALLOWEEN:

SONG THE HALLOWEEN (OTHER MANNER)

|

HALLOWEEN (INTERPRETATED IN ENGLISH)

|

ˈbɔɪz ənd gɜːlz əv ˈevrɪ eɪʤ

ˈwʊdnt jʊ laɪk tə siː ˈsʌmθɪŋ streɪnʤ

kʌm wɪð ʌs ənd jʊ wɪl siː

ðɪs ˈaʊə taʊn əv Halloween

ðɪs ɪz Halloween

ðɪs ɪz Halloween

ˈpʌmpkɪnz skriːm ɪn ðə ded əv naɪt

ðɪs ɪz Halloween ˈevrɪbɒdɪ meɪk ə siːn

trɪk ə triːt tɪl ðiː (neighbors) ˈgɒnə daɪ əv fraɪt

ɪts ˈaʊə taʊn

ˈevrɪbɒdɪ skriːm

ɪn ðɪs taʊn əv Halloween

aɪ æm ðə wʌn ˈhaɪdɪŋ ˈʌndə jə bed

Tiːθ graʊnd ʃɑːp ənd ˈaɪz ˈgləʊɪŋ red

aɪ æm ðə wʌn ˈhaɪdɪŋ ˈʌndə jə steəz

ˈfɪŋgəz laɪk sneɪks ənd ˈspaɪdəz ɪn maɪ heə

ðɪs ɪz Halloween ðɪs ɪz Halloween Halloween

Halloween Halloween

Halloween

ɪn ðɪs taʊn wi kɔːl həʊm

ˈevrɪwʌn heɪl tə ðə ˈpʌmpkɪn sɒŋ

ɪn ðɪs taʊn dəʊnt wi lʌv ɪt naʊ/

ˈevrɪbɒdɪz ˈweɪtɪŋ fə ðə nekst səˈpraɪz

raʊnd ðæt ˈkɔːnə mæn

ˈhaɪdɪŋ ɪn ðə træʃ kæn

ˈsʌmθɪŋz ˈweɪtɪŋ naʊ tə paʊns ənd haʊ juːl skriːm

skriːm ðɪs ɪz (Halloween)

red ('n') blæk ˈslaɪmɪ griːn ɑːnt jʊ skeəd/

wel ðæts ʤʌst faɪn

seɪ ɪt wʌns seɪ ɪt twaɪs

teɪk ðə ʧɑːns ənd rəʊl ðə daɪs

raɪd wɪð ðə muːn ɪn ðə ded əv naɪt

ˈevrɪbɒdɪ skriːm ˈevrɪbɒdɪ skriːm ɪn ˈaʊə

taʊn əv Halloween

aɪ æm ðə klaʊn wɪð ðiː tərəˈweɪ feɪs

hɪə ɪn ə flæʃ ənd gɒn wɪˈðaʊt ə treɪs

aɪ æm ðə huː wen jʊ kɔːl huːz ðeə/

aɪ æm ðə wɪnd ˈbləʊɪŋ θruː jə heə

aɪ æm ðə ˈʃædəʊ ɒn ðə muːn ət naɪt

ˈfɪlɪŋ jə driːmz tə ðə ˈbrɪm wɪð fraɪt

ðɪs ɪz Halloween ðɪs ɪz Halloween Halloween

Halloween Halloween

Halloween

ˈtendə lʌmp lɪŋz ˈevrɪweə

laɪfs nəʊ fʌn wɪˈðaʊt ə gʊd skeə

ðæts ˈaʊə ʤɒb bʌt wɪə nɒt

miːn

ɪn ˈaʊə taʊn əv (Halloween)

ɪn ðɪs taʊn dəʊnt wi lʌv ɪt naʊ

ˈevrɪwʌnz ˈweɪtɪŋ fə ðə nekst səˈpraɪz

ˈskelɪtn ʤæk maɪt kæʧ jʊ ɪn ðə bæk

ənd skriːm laɪk ə bænˈʃiː

meɪk jʊ ʤʌmp aʊt əv jə skɪn

ðɪs ɪz (Halloween) ˈevrɪbɒdɪ skriːm

wəʊnt (ya) pliːz meɪk weɪ fər ə ˈverɪ ˈspeʃəl gaɪ

ˈaʊə mæn ʤæk ɪz kɪŋ əv ðə ˈpʌmpkɪn pæʧ

ˈevrɪwʌn heɪl tə ðə ˈpʌmpkɪn kɪŋ naʊ/

ðɪs ɪz (Halloween) ðɪs ɪz Halloween Halloween

Halloween Halloween

Halloween

/ɪn ðɪs pleɪs wi kɔːl həʊm ˈevrɪwʌn heɪl tə ðə ˈpʌmpkɪn sɒŋ/

|

Boys and

girls of every age

Woudn’t

you like to see something

Strange

Came was

us and you will see

This our

town of Halloween

This is

Halloween

This is

Halloween

Pumpkins

scream in the bed of nat

This is

Halloween everybody make a seen

Trick or

treat try is : (neighbors) gone day of

frate

It’s our

town everybody scream

In this

town of Halloween

I am the

want hating under the bed

The around

shape and ‘ice’ eleven red

I

am the want hating under the streets

Fingers

like snacks and spiders in my head

This

is Halloween , this is Halloween, Halloween Halloween, Halloween, Halloween

In

this town We could home

Everyone

jail to the pumkin song

In

this town don’t we love it now

Everybody

‘ s waiting for the next surprise

Round

sad corney man

Hating

in the trash can

Something

waiting now the pounds and how your scream

Scream

this is (Halloween)

Red

and black slame green aren’t you skied

Well

seat does fine

Say

it ones , say it ones

Take

the thanks and real the days

Read

with the moon, in the bed of night

Everybody

scream, everybody scream in our town of

I

am the clown with did there way face

High

in a flag and gone without a trees

I

am the hot when you call hurts deal

I

am the wind blowing truth jay hill

I

am the shadow in the moon at night

Feeling

yet dreams to the brain with frate

This

is Halloween , this is Halloween, Halloween Halloween, Halloween, Halloween

Tendy lamp night

everyway

Lifes

new fun without a good skin

That’s our grab bat way not mint

In

our town of (Halloween)

In

this town doesn’t we love it now

Everyones

waiting for the next surprise

Skeleton

joke met catch you in the back

And

scream like a benefit

Make

you jump out of the skin

This

is (Halloween) , everybody scream

Want

please make way for a very special day

Our

man joke is king of the pumpkin king now

This

is Halloween , this is Halloween, Halloween Halloween, Halloween, Halloween

In

this place we could home everyone jail to the pumpkin song

|

IDENTIFICATION INTO THE SONG ABOUT THE TEXT :

- LINKING

- LINKING OF

VOWEL TO VOWEL

- LINKING OF

CONSONANT TO CONSONANT (GEMINATION)

- ELISION

- SYNCOPE

- APHESIS

- ASSIMILATION

- PROGRESIVE ASSIMILATION

- REGRESSIVE ASSIMILATION

CORECTION OF THE SONG THIS IS HALLOWEEN - TIM BURTON - WEEK 14:

|

THE

HALLOWEEN SONG - PHONETIC PART

|

THE HALLOWEEN SONG –

IDENTIFICATION PART

|

THIS HALLOWEEN –

ORIGINAL SONG

|

|

bɔɪz ənd gɜːlz əv ˈevrɪ eɪʤ

ˈwʊdnt jʊ laɪk tə siː ˈsʌmθɪŋ streɪnʤ

kʌm

wɪð ʌs ənd jʊ wɪl siː

ðɪs

ˈaʊə taʊn əv Halloween

ðɪs

ɪz Halloween,

ðɪs

ɪz Halloween

ˈpʌmpkɪnz skriːm ɪn ðə ded əv naɪt

ðɪs ɪz Halloween ˈevrɪbɒdɪ meɪk ə siːn

trɪk

ə triːt tɪl ðiː (neighbors) ˈgɒnə

daɪ əv fraɪt

ɪts

ˈaʊə

taʊn ˈevrɪbɒdɪ skriːm

ɪn ðɪs taʊn əv Halloween

aɪ æm ðə wʌn ˈhaɪdɪŋ ˈʌndə jə bed

Tiːθ graʊnd ʃɑːp ənd

ˈaɪz ˈgləʊɪŋ

red

aɪ

æm ðə wʌn ˈhaɪdɪŋ ˈʌndə jə steəz

ˈfɪŋgəz laɪk sneɪks ənd ˈspaɪdəz

ɪn maɪ heə

ðɪs

ɪz Halloween ðɪs ɪz Halloween

Halloween! Halloween! Halloween! Halloween!

ɪn ðɪs taʊn wi kɔːl həʊm

ˈevrɪwʌn heɪl tə ðə ˈpʌmpkɪn sɒŋ

ɪn

ðɪs taʊn dəʊnt wi lʌv ɪt naʊ/

ˈevrɪbɒdɪz ˈweɪtɪŋ fə ðə nekst

səˈpraɪz

raʊnd

ðæt ˈkɔːnə mæn

ˈhaɪdɪŋ ɪn ðə træʃ kæn

ˈsʌmθɪŋz ˈweɪtɪŋ naʊ tə paʊns ənd

haʊ juːl skriːm

skriːm

ðɪs ɪz (Halloween)

red

('n') blæk ˈslaɪmɪ griːn ɑːnt jʊ skeəd/

wel ðæts ʤʌst faɪn

seɪ ɪt wʌns seɪ ɪt twaɪs

teɪk

ðə ʧɑːns ənd rəʊl ðə daɪs

raɪd wɪð ðə muːn ɪn ðə ded əv naɪt

ˈevrɪbɒdɪ skriːm ˈevrɪbɒdɪ skriːm ɪn ˈaʊə taʊn əv

Halloween

aɪ

æm ðə klaʊn wɪð ðiː

tərəˈweɪ feɪs

hɪə ɪn ə flæʃ ənd gɒn wɪˈðaʊt ə treɪs

aɪ æm ðə huː wen jʊ kɔːl huːz

ðeə/

aɪ

æm ðə wɪnd ˈbləʊɪŋ θruː jə heə

aɪ

æm ðə ˈʃædəʊ ɒn ðə muːn ət naɪt

ˈfɪlɪŋ jə driːmz tə ðə ˈbrɪm wɪð fraɪt

ðɪs

ɪz Halloween ðɪs ɪz Halloween

Halloween,Halloween Halloween Halloween

ˈtendə

lʌmp lɪŋz ˈevrɪweə

laɪfs

nəʊ fʌn wɪˈðaʊt ə gʊd skeə

ðæts ˈaʊə ʤɒb bʌt wɪə nɒt miːn

ɪn ˈaʊə taʊn əv (Halloween)

ɪn

ðɪs taʊn

dəʊnt

wi lʌv ɪt naʊ

ˈevrɪwʌnz ˈweɪtɪŋ fə ðə nekst

səˈpraɪz

ˈskelɪtn

ʤæk maɪt kæʧ jʊ ɪn

ðə bæk

ənd

skriːm laɪk ə bænˈʃiː

meɪk jʊ ʤʌmp aʊt əv jə skɪn

ðɪs

ɪz (Halloween) ˈevrɪbɒdɪ skriːm

wəʊnt

(ya) pliːz meɪk weɪ fər ə ˈverɪ ˈspeʃəl gaɪ

ˈaʊə

mæn ʤæk ɪz kɪŋ əv ðə ˈpʌmpkɪn pæʧ

ˈevrɪwʌn heɪl tə ðə ˈpʌmpkɪn kɪŋ naʊ/

ðɪs

ɪz (Halloween) ðɪs ɪz Halloween

Halloween

Halloween

Halloween Halloween

/ɪn ðɪs pleɪs wi kɔːl həʊm ˈevrɪwʌn heɪl

tə ðə ˈpʌmpkɪn sɒŋ/

|

Boys

and girls of every age

Woudn’t

you like to see something

Strange

Came

was us and you will see

This

our town of Halloween

This

is Halloween

This

is Halloween

Pumpkins

scream in the bed of nat

This

is Halloween everybody make a seen

Trick

or treat try is : (neighbors) gone day of frate

It’s

our town everybody scream

In

this town of Halloween

I am

the want hating under the bed

The

around shape and ‘ice’ eleven red

I am

the want hating under the streets

Fingers

like snacks and spiders in my head

This

is Halloween , this is Halloween, Halloween Halloween, Halloween, Halloween

In

this town We could home

Everyone

jail to the pumkin song

In

this town don’t we love it now

Everybody

‘ s waiting for the next

surprise

Round

sad corney man

Hating

in the trash can

Something

waiting now the pounds and how your scream

Scream

this is (Halloween)

Red

and black slame green aren’t you skied

Well

seat does fine

Say

it ones , say it ones

Take

the thanks and real the days

Read

with the moon, in the bed of night

Everybody

scream, everybody scream in our town of Halloween

I am

the clown with did there way face

High

in a flag and gone without a trees

I am

the hot when you call hurts deal

I am

the wind blowing truth jay hill

I am

the shadow in the moon at night

Feeling

yet dreams to the brain with frate

This

is Halloween , this is Halloween, Halloween Halloween, Halloween, Halloween

Tendy

lamp night everyway

Lifes

new fun without a good skin

That’s our grab bat way not mint

In

our town of (Halloween)

In

this town doesn’t we love it now

Everyones

waiting for the next surprise

Skeleton

joke met catch you in the back

And

scream like a benefit

Make

you jump out of the skin

This

is (Halloween) , everybody scream

Want

please make way for a very special day

Our

man joke is king of the pumpkin king now

This

is Halloween , this is Halloween, Halloween Halloween, Halloween, Halloween

In

this place we could home everyone jail to the pumpkin song

|

Boys and girls of every

age

Wouldn't you like to see something strange? Come with us and you will see This, our town of Halloween This is Halloween, this is Halloween Pumpkins scream in the dead of night

This is Halloween,

everybody make a scene

Trick or treat till the neighbors gonna die of fright It's our town, everybody scream In this town of Halloween I am the one hiding under your bed Teeth ground sharp and eyes glowing red I am the one hiding under your stairs Fingers like snakes and spiders in my hair This is Halloween, this is Halloween Halloween! Halloween! Halloween! Halloween! In this town we call home Everyone hail to the pumpkin song In this town, don't we love it now? Everybody's waiting for the next surprise Round that corner, man hiding in the trash can Something's waiting now to pounce, and how you'll scream Scream! This is Halloween Red 'n' black, slimy green

Aren't you scared?

Well, that's just fine Say it once, say it twice Take the chance and roll the dice Ride with the moon in the dead of night Everybody scream, everybody scream In our town of Halloween I am the clown with the tear-away face Here in a flash and gone without a trace I am the "who" when you call, "Who's there?" I am the wind blowing through your hair I am the shadow on the moon at night Filling your dreams to the brim with fright

This is Halloween, this

is Halloween

Halloween! Halloween! Halloween! Halloween! Tender lump lings everywhere Life's no fun without a good scare That's our job, but we're not mean in our town of Halloween

In this town

Don't we love it now?

Everyone's waiting for the next surprise

Skeleton Jack might catch

you in the back

And scream like a banshee Make you jump out of your skin This is Halloween, everybody scream Won't ya please make way for a very special guy Our man jack is king of the pumpkin patch Everyone hail to the Pumpkin King now This is Halloween, this is Halloween Halloween! Halloween! Halloween! Halloween! In this town we call home Everyone hail to the pumpkin song(65). |

LINKING VOWEL TO VOWEL: RED

RESYLLABIFICATION: YELLOW

GENIMATION: GREEN

SYNCOPE: BLUE

ELISSION: VIOLET

SIMPLIFICATION OF CONSONATS CLUSTERS: ORANGE

INTONATION AND SUPRASEGMENTALS - WEEK 15:

INTONATION:

Intonation describes how the voice rises and falls in speech. The three main patterns of intonation in English are: falling intonation, rising intonation and fall-rise intonation.

Falling intonation

Falling intonation describes how the voice falls on the final stressed syllable of a phrase or a group of words. A falling intonation is very common in wh-questions.

EXAMPLES:

Where’s the nearest p↘ost-office?

What time does the film f↘inish?

We also use falling intonation when we say something definite, or when we want to be very clear about something:

EXAMPLES:

I think we are completely l↘ost.

OK, here’s the magaz↘ine you wanted.

Rising intonation

Rising intonation describes how the voice rises at the end of a sentence. Rising intonation is common in yes-no questions:

EXAMPLES:

I hear the Health Centre is expanding. So, is that the new d↗octor?

Are you th↗irsty?

Fall-rise intonation

Fall-rise intonation describes how the voice falls and then rises. We use fall-rise intonation at the end of statements when we want to say that we are not sure, or when we may have more to add:

EXAMPLES:

I do↘n’t support any football team at the m↘om↗ent. (but I may change my mind in future).

It rained every day in the firs↘t w↗eek. (but things improved after that).

We use fall-rise intonation with questions, especially when we request information or invite somebody to do or to have something. The intonation pattern makes the questions sound more polite:

EXAMPLES:

Is this your cam↘er↗a?

Would you like another co↘ff↗ee?(57)

The Melody of a Language

"Intonation is the melody or music of a language. It refers to the way the voice rises and falls as we speak. How might we tell someone that it's raining?

It's raining, isn't it? (or 'innit,' perhaps)We're telling the person, so we give our speech a 'telling' melody. The pitch-level of our voice falls and we sound as if we know what we're talking about. We're making a statement. But now imagine we don't know if it's raining or not. We think it might be, so we're asking someone to check. We can use the same words--but note the question-mark, this time:

It's raining, isn't it?Now we're asking the person, so we give our speech an 'asking' melody. The pitch-level of our voice rises and we sound as if we're asking a question."(59)

SUPRASEGMENTALS:

In speech, a phonological property of more than one sound segment. Also called nonsegmental.

As discussed in Examples and Observations below, suprasegmental information applies to several different linguistic phenomena (such as pitch, duration, and loudness). Suprasegmentals are often regarded as the "musical" aspects of speech.

The term suprasegmental (referring to functions that are "over" vowelsand consonants) was coined by American structuralists in the 1940s.

The term suprasegmental (referring to functions that are "over" vowelsand consonants) was coined by American structuralists in the 1940s.

The segments of spoken language are the vowels and the consonants, which combine to produce syllables, words, and sentences.

But at the same time as we articulate these segments, our pronunciation varies in other respects. We make use of a wide range of tones of voice, which change the meaning of what we way in a variety of different ways. Suprasegmental features operate over longer stretches of speech, such as rhythm and voice quality as opposed to segmental features, which are the individual sounds.

Students of language and those who plan careers in language teaching, coaching, therapy, acting, and speaking will benefit greatly from understanding how they can influence meaning by things like length, intonation, stress, and tone and other suprasegmental features.

Length - the amount of time it takes to produce a sound

Some sounds are longer than others.| English: | beat vs. bead |

But in other languages, vowel length actually changes the meaning of words. Therefore, pronunciation of the lengthened sound is very important because the word means something completely different. Study these examples in Hawaiian. Length in Hawaiian is indicated with the diacritical mark that looks like a dash over the vowel, called a kahakō.

| Hawaiian: | kau "to place" |

| kāu "to belong to you" | |

| lolo "brain" | |

| lōlō "slang - hardheaded | |

| kala "to forgive" | |

| kāla "money" | |

| ka lā "the sun" | |

| pau "finished" | |

| pa'u "soot" | |

| pa'ū "skirt" |

| English: | Should I leave now? |

| Yes. (snipped, implies irritation) | |

| Ye-e-e-e-s-s-s-s (implies thoughtfulness) |

Intonation - the rising and falling of the voice (pitch) over a stretch of sentence

If pitch varies over an entire phrase or sentence, we call the different pitch curves by the term intonation. Intonation conveys the speaker's attitude or feelings. In other words, intonation can convey anger, sarcasm, or various emotions.How do these sentences - with the exact same words -- mean very different things with different intonation?

| John told me to leave. | (normal intonation) |

| John told me to leave. | (emphasis on John: John, not Mike) |

| John told me to leave. | (emphasis on told: told, not asked nicely) |

| John told me to leave. | (emphasis on me: me, not you or Mary) |

| John told me to leave. | (emphasis on leave: leave, not stay) |

Other languages don't use intonation in this way. "John told me to leave" is "Jose me mando a salir" in Spanish. But it's not possible to say Jose me mando a salir or Jose me mando a salir, as we can in English. Instead of raising your voice to emphasize a word, Spanish uses word order and places the word to be emphasized at the end of the sentence (note: the written accent marks are left out below):

| John told me to leave. | Jose me mando a salir. | (normal intonation) |

| John told me to leave. | Me mando a salir a José. | (emphasis on José) |

| John told me to leave. | Jose me mando a salir a mi. | (emphasis on me) |

Stress (tense or lax syllables) and Juncture (pauses within sentences to separate words and meaning)

In English, the stress you place on a syllable can change the meaning of a word.| White House (the US President's house) | white house (a house that's white) |

| nitrate | night rate |

| record (noun) | record (verb) |

| address (noun) | address (verb) |

When combined with pausing after certain words, the meaning of the whole sentence can completely change. Click the underlined words to hear the phrases, paying attention to the pauses. Sometimes the resulting change of meaning is funny, as examples 1 and 2 below demonstrate. (Click the underlined words to hear them pronounced.)

Example 1: A tight-rope walker is an acrobat. A tight ropewalker is a drunk ropewalker.

Tone - the rising and falling of pitch in a syllable

If the pitch of a single syllable or word has the effect of influencing the meaning of the word, we call the different pitch distributions by the term tone. Every language uses pitch as intonation, but only some languages use it as tone. There are two basic types of tones in tone languages.- Register tones are measured by contrasts in the absolute pitch of different syllables. Register tones may be high, mid, or low. Many West African languages use contrasts of high mid and low tones to distinguish word meaning: Zulu, Hausa, Yoruba, Navajo, Apache.

- Contour tones are tones involving a pitch shift upward or downward on a single syllable. Many languages of East and Southeast Asia use contour tones, the best known being Mandarin Chinese.

Mandarin has four tones for [ma:]. Each word means something different ("mother," "hemp," "horse," "scold.") Click here to listen to the pronunciation of four tones in Mandarin, including [ma:],(64)

WEEK 1:

1 Color.(n.d.)Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://www.skidmore.edu/~hfoley/Perc11.htm

2 Department of Linguistics. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://clas.mq.edu.au/speech/phonetics/transcription/ipa/ipa_consonant.html

3 English Vowel Sounds. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://usefulenglish.ru/phonetics/english-vowel-sounds4 Theory of Language. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://www.mind.ilstu.edu/curriculum/theory_of_language/23/

5 What Are the Consonant Sounds and Letters in English? (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://grammar.about.com/od/c/g/consonaterm.htmWEEK 2:

6 ABC FAST Phonics - 11: Long and Short Vowels. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://www.abcfastphonics.com/long-short-vowels.html

7 (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/diphthong

8 (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/learningenglish/grammar/pron/features/connected.shtm

WEEK 3 & 5

9 What Are Consonant Clusters in English? (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://grammar.about.com/od/c/g/Consonant-Cluster-Cc.htm

10 What Are the Consonant Sounds and Letters in English? (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://grammar.about.com/od/c/g/consonaterm.htm

WEEK 4:

11 Classification and meaning of every consonant,manners,sounds. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://www.taringa.net/posts/info/14765679/Classification-and-meaning-of-every-consonant-manners-sounds.html

12 Trask, R. (2006). Mind the gaffe!: A troubleshooter's guide to English style and usage. New York: Harper.

13 What is a consonant sound? (2013, May 22). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from https://pronunciationstudio.com/consonant-sound/

WEEK 6:

14 Diphthongs. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://home.hib.no/al/engelsk/seksjon/SOFF-MASTER/Diphthongs.htm

15 Diphthong - Dictionary Definition. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/diphthong

16 English teaching worksheets: Diphthongs. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://www.eslprintables.com/grammar_worksheets/phonetics/diphthongs

17 Minimal Pairs. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from https://www.englishclub.com/pronunciation/minimal-pairs.htm

18 Minimal pairs. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from https://notendur.hi.is/peturk/KENNSLA/02/TOP/Minimal pairs.html

19 (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/diphthong

20 (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://agrega.juntadeandalucia.es/repositorio/27052010/b1/es-an_2010052713_9102852/ODE-9f86ef91-8db3-3312-8525-1a97db8f986e/4_cowards_die_many_times.html

21 PHONOLOGY III. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://phonologythree.blogspot.com.co/2012/05/chapter-32-diphthongs-and-triphthongs.html

22 Roach, P, (2009), English Phonetics and Phonology, Ed .Cambrigde University Press, Cambridge , UK.

23 Triphthongs. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Triphthongs

24 Up, Up, & Away Phonology! (2012, November 10). Retrieved November 17, 2015. from

http://crazyspeechworld.com/2012/11/up-up-away-phonology.html

WEEK 8:

25 Crystal, D. (2003). A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics (4th ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

26 Denham, K., & Lobeck, A. (2010). Linguistics for everyone: An introduction. Boston, MA: Wadsworth/ Cengage Learning.

27 Finegan, E. (2012). Language: Its Structure and Use, (6th ed). Wadsworth

28 Knowles, G.,& McArthur, T. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the English Language, edited by Tom McArthur. Oxford University Press,

29 Parker, F., & Riley, K , (1994). Linguistics for Non-Linguists, (2nd ed.). Allyn and Bacon

30 What Is a Syllable? (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://grammar.about.com/od/rs/g/syllableterm.htm

31 What is Word Stress? (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from https://www.englishclub.com/pronunciation/word-stress-2.htm

WEEK 9:

31A Assimilation

(phonetics). (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://grammar.about.com/od/ab/g/assimilationterm.htm

32 Algeo, J, (1999). "Vocabulary," in The

Cambridge History of the English Language, (Volume IV, ed. by Suzanne Romaine).

Cambridge Univ. Press

33 Burridge, K, (2011). Gift of the Gob: Morsels of English Language

History: Australia: HarperCollins

40 ,

34 Collins, B., & Mees, I. (2013). Practical Phonetics

and Phonology: A Resource Book for Students, (3rd ed). Routledge.

35 Denham, K., & Lobeck, A. (2010). Linguistics for

everyone: An introduction. Boston, MA: Wadsworth/ Cengage Learning

36 Elision in Speech. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015,

from http://grammar.about.com/od/e/g/elisionterm.htm

37 ELISION , WEAK WORDS AND ASSIMILATION. (n.d.). Retrieved

November 17, 2015, from https://bubbl.us/?h=2d1b9d/5a9cb1/29GWVDx8QaK0I&r=460553451

38 Jones, D., & Roach, P. (2006). Cambridge English

pronouncing dictionary: With CD-ROM (17th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

39 Kansakar Tej. (1998) A Course in English Phonetics.

Orient Blackswan

SPIDER MAP:

40 Section 1: What is Prosody? (n.d.). Retrieved November

17, 2015, from http://www.cs.columbia.edu/~julia/courses/CS4706/chilin.htm

41 Salzmann, Z. (2004). Language, culture and society : An

introduction to linguistic anthropology (3rd ed.). Boulder (CO): Westview

Press.

42 Weak forms. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/weak-formsWEEK 10:

43 Intonation - gramática inglés en. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015,

from http://dictionary.cambridge.org/es/gramatica/gramatica-britanica/intonation

44 Linguistics 001 -- Lecture 15 -- Language

and Gender. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://www.ling.upenn.edu/courses/Fall_2011/ling001/gender.html

45 Making a chart to help us learn the tone

rules in Thai. Wow, they are ridiculously complicated. I appreciate Hmong more.

| Travis Gore: Illustration and Design. (2013, June 23). Retrieved November 17,

2015, from http://travisgore.com/making-a-chart-to-help-us-learn-the-tone-rules-in-thai-wow-they-are-ridiculously-complicated-i-appreciate-hmong-more/

46 Part 6.0: Using PRAAT to analyze tonal languages. (2014, June 6). Retrieved

November 17, 2015, from

https://colangpraat.wordpress.com/part-6-0-using-praat-to-analyze-tonal-languages/

47 Tone | speech. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://global.britannica.com/topic/tone-speech

48 Tones and Accents. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://www.internationalphoneticalphabet.org/ipa-charts/tones-and-accents/

WEEK 14:

49 Clear Language, Clear Mind. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://emilkirkegaard.dk/en/?tag=english-spelling-reform

50 Linguistics hanoi

university. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://www.slideshare.net/tungnth/linguistics-hanoi-university

51 (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://www.rachaelanne.net/teaching/uev/uev4.doc

52 (n.d.). Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://www.incatena.org/viewtopic.php?f=4&t=39704

53 Processes of Connected Speech. (n.d.).

Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://www.slideshare.net/Adri_Gonzalez/processes-of-connected-speech

54 Rachael-Anne

Knight, 2003, University of Surrey - Roehampton Understanding English

Variation, Week 4

55 Speech phenomena.

(n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://www.slideshare.net/Kengiro/speech-phenomena

56 Sandhi. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://www.elportaldelaindia.com/El_Portal_de_la_India_Antigua/Sandhi.html

WEEK 15:

57 Burton Tim. (n.d.). Retrieved

November 17, 2015, from http://www.metrolyrics.com/this-is-halloween-lyrics-burton-tim.html

58 Crystal,

D. (n.d.). A

little book of language.

59Intonation - gramática inglés en.

(n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://dictionary.cambridge.org/es/gramatica/gramatica-britanica/intonation

60IPA Help

Preview. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://www-01.sil.org/computing/ipahelp/ipasupra2.htm

61Linguistics.

(n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://linguistics2012ananeira.blogspot.com.co/2012/06/intonation.html

62 Mod 3 Lesson 3.7 Suprasegmentals. (n.d.). Retrieved

November 17, 2015, from

63Stress-timed languages. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015,

from http://www.snipview.com/q/Stress-timed_languages

64 What Is Intonation in English Speech? (n.d.). Retrieved

November 17, 2015, from http://grammar.about.com/od/il/g/intonationterm.htm

65 What Are

Suprasegmentals in Speech? (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://grammar.about.com/od/rs/g/Suprasegmental.htm